To Whom It May Concern:

It gives me great pleasure to recommend Ethan for admission to your institution. Ethan enrolled in three of my classes through his high school career. He is a student who has achieved academic success and possesses great potential. He has inspired me and students in class with his work ethic, his writing ability and his thoughtful commentary. You will be pleased to admit him to your upcoming class.

Blah, Blah, Blah. That induces as much boredom reading it as it did writing it. But my college recommendation letters often read like that. What am I doing? I find myself wondering about the entire recommendation letter process.

By the time I let the computer cool down, I will have written 40+ recommendation letters this application season. Interestingly, it occurs that these letters actually represent a form of summative assessment. Though the students tend not to see them as such, these really afford the teacher the opportunity to give summative assessments of their students that are not in any way connected to points, grades and all the other elements of assessment.

I typically don’t share the letter with students. However, if I truly do value it as a summative assessment, then it seems I should share it with them. I should use it to provide teachable insights with the students and let them know this is how I see them not only as a students, but also as people. The comments and observations in the letters represent their strengths.

In the Greater Madison Writing Project we promote the C3WP (College Career Community Writers Program) protocols of argument writing to our project members. One of the elements that always stands out focuses on strengths in the students’ writing. So often in assessment we look at what doesn’t appear, or weaknesses. We get locked in to the deficit framework, sometimes to the neglect of the good. The National Writing Project rubric, though, suggests instead that teachers approach assessment from a point of strengths as opposed to weaknesses. We can learn and grow as much and likely more from emphasis on what we do well than a laser focus on what we have done less well.

When I write a letter of recommendation, I try to present insights into the ability of the student and important qualities of character. With thoughtful contemplation, this recommendation letter could become a clearer snapshot of the student’s abilities and work in my class than numbers on a page.

As I get excited about the possibilities of writing a letter not just for my students, but a letter to my students, I stop cold. I often have wondered about the actual, true importance of the letter in the student’s application.. And does it really matter? Many of my colleagues have come to believe it doesn’t. They put as little actual effort into the letter as possible. They believe admissions officers likely glance at the letter in search of red flags. So then I wonder if writing this kind of letter enhances admission chances. It may not. It will definitely take more time to write. If I choose to write a true reflection of the total student, I would want it to be more than just a writing exercise.

I like so much better the idea of writing a letter to my student, rather than a letter to some anonymous admissions officer, who is skimming through lines of type, eyes bleary, keeping a close count on their daily numbers of applications read and scored.

So Dear Ethan, or Dear Nana, Dear Shamyon, Dear Naia, Dear Eva, Dear Hannah, Dear Edwin, Dear All: This is my assessment of you. Let me tell you first of all, what a privilege it has been to teach you in this class and what a bright future you have ahead of you. Though I may not have taken the time to share these thoughts with you in class, I want you to know I always appreciated you and all that you did. Not only are you a thoughtful student, you are a fine and wonderful person. You should always know and believe that about yourself.

I would have loved to receive a letter like that from a teacher.

All right. I’m committed to the idea.

This is what my recommendation letters will look like:

To Whom It May Concern:

Dear Ethan,

While your friends socialized loudly before school, you leaned against a locker, studying a textbook on robotics. We don’t offer courses in Robotics, but you want to learn as much as possible to become a more effective leader of your robotics team. That is so you. You commit. Wholly. Completely. You stand out as one of those students who possesses this insatiable intellectual curiosity. You strive to constantly learn and grow, and what you want to learn crosses all spectrums of knowledge. You just want to know as much as possible. You have said you only get one opportunity to live your life. You might as well get as much out of it as you can. Everybody should adopt your philosophy on living. Interestingly, I wouldn’t classify you as a bookworm or a drudge, though. You possess a vast friend base. You thrive in social interactions with friends or teammates, whether they are swimming teammates or members of the robotics team. You draw people to you. Your laughter lights up a room. Your future looks so bright. It’s time for you to go out into the world and get after it.

Sincerely,

Mark Nepper

Mark Nepper teaches in Madison, Wisconsin and works with high schoolers as well as practicing teachers. While he has been teaching for over 30 years, he is not quite ready to retire.

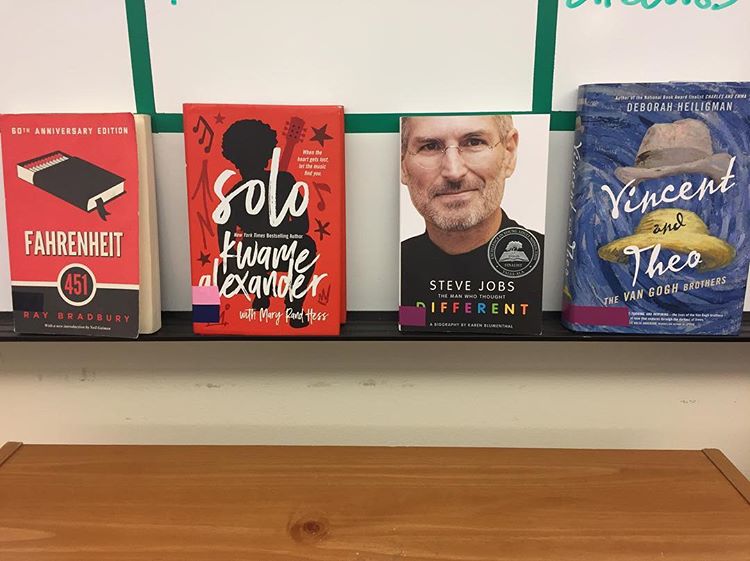

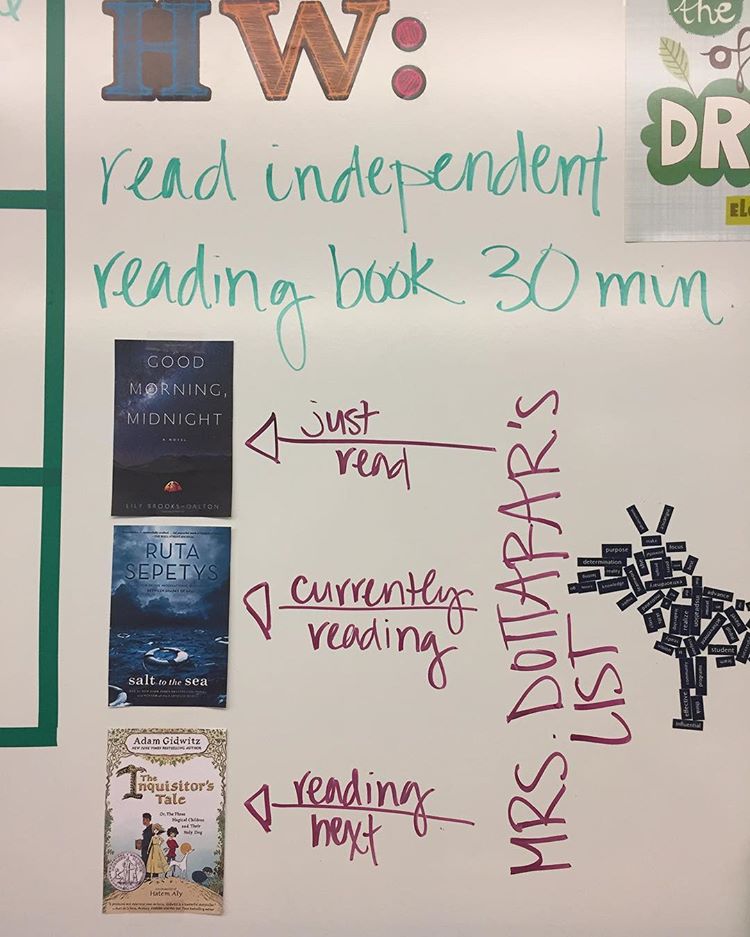

with books: What I just read, What I am currently reading, and What I plan to read next. Next to each phrase I had an arrow and a copy of the book jacket so students could see my book list. I didn’t do that this year because I didn’t have white board space.

with books: What I just read, What I am currently reading, and What I plan to read next. Next to each phrase I had an arrow and a copy of the book jacket so students could see my book list. I didn’t do that this year because I didn’t have white board space.  Twice a year, right before Christmas Break and right before school is out, I have students fill out a recommendation form on books they enjoyed and think others might like. It goes in a binder organized by genre. However, students do not share these recommendations prior to turning them in. Why have I not done that? Not sure. It was kind-of like checking something off my to-do list. In this area, I plan to have students share out books they wrote down on that sheet of paper before turning in.

Twice a year, right before Christmas Break and right before school is out, I have students fill out a recommendation form on books they enjoyed and think others might like. It goes in a binder organized by genre. However, students do not share these recommendations prior to turning them in. Why have I not done that? Not sure. It was kind-of like checking something off my to-do list. In this area, I plan to have students share out books they wrote down on that sheet of paper before turning in.